The award-winning writer’s latest book explores themes of oppression in a patriarchal society

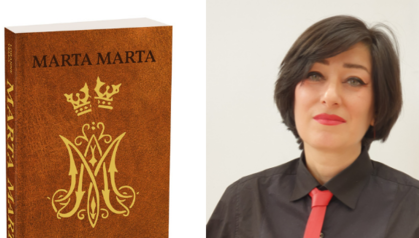

If I were to place feminism and LGBTIQ rights within the same sentence, would you be surprised? Many would. And yet, in a world where the patriarchy remains firmly entrenched, they are very much the same side of the coin. This is the premise behind Marta Marta, a new publication by Loranne Vella that joins the Maltese books landscape. Vella, of course, is the name behind the award-winning Rokit, and so many other beloved titles. I caught up with Loranne to find out more about Marta Marta and the issues and beliefs that informed the novel. Below, she answers some of my questions.

Who is Marta and what does she stand for?

The name Marta comes from Aramaic and means the lady and mistress of the house. The biblical Marta in Luke 10.38-42 stands for the woman who is actively involved in keeping her house clean and proper. However, in Luke’s story she is positioned against her sister Mary, who chooses to stop whatever she was doing in order to sit down and listen to the words of Jesus, and for this, Marta is scolded whilst Mary is praised.

Historically and traditionally, a woman was expected to become either a Marta – the woman who marries and stays home to take care of her husband’s house and children – or a Mary, the woman who chooses not to marry but to take holy orders and dedicate her life to spiritual contemplation. This binarity was broken for a while in Northern Europe with the appearance of the beguines who chose to neither marry nor become nuns, but rather to buy property and live within a walled and safe space inside the city. As beguines, they could, at any point, decide to leave this community and get married or become nuns, without asking any man’s permission to do so. They were truly mistresses of their own house.

The house in Marta Marta, in which we find the five main characters of the novel, plays a very important role because, like the beguinage in Medieval Europe, it is a safe space as well as a laboratory in which anything thought of as liberating to these characters becomes possible.

Marta Marta – how does it relate to the claim that there is no need for feminism and LGBTIQ rights nowadays?

Notwithstanding that it is bizarre to treat LGBTIQ rights as separate issues from women’s rights, this is actually the case locally. Happily, much has taken place in Malta with regards to LGBTIQ rights throughout the last couple of decades. And yet, it is amazing to see that the feminist question is yet to be properly addressed. It is astonishing to see how Maltese society continues to thrive on and defend patriarchal structures: the Church, the state, the nuclear family – structures which are immensely oppressive towards women – while at the same time promoting LGBTIQ rights.

Some would say that women’s rights are no longer an issue, without realising that women’s rights are not limited to the right to vote or the right to work and the right to equal pay anymore, although these were much needed just a few decades ago. In spite of these developments towards equality, the oppression is still there. The oppression that forces women to believe that they should, first and foremost, become wives and mothers, carers of the family – the oppression that makes us believe that that is our ‘natural’ role.

The oppression that leads women to be careful when enjoying sex too much as it makes them sound like whores. The oppression that still exists whereby women choose to be careful when stating their minds as they will most probably be labelled hysterical, or mad. The oppression that constrains women into being careful when fighting for what should be theirs as by doing so they will no longer be thought of as womanly.

The oppression that leads women to having to work twice as hard to prove their worth when it would take nothing for a man to prove himself, society is still mostly on his side. It is scary when these things are taken for granted to the extent that the oppression becomes invisible and internalised and we end up thinking it is our normal and natural condition to be oppressed in this way.

Marta Marta deals with oppression related to gender that can come in the form of patriarchal oppression of male over female, but this also sheds light on another type of oppression: that which recognises only fixed binary states of being – male or female – with the added consequence that the first category has always dominated the second. We tend to forget that it was Man who decided to label people, animals and things around him only as either male or female, and then stated that it was nature that made things that way. Marta Marta chooses instead to celebrate diversity, plurality, fluidity and non-binarity.

What is the approach taken by Marta Marta towards the lack of reproductive rights in Malta?

Any person not granted the right to save themselves is oppressed. The fact that Malta completely refuses to start a debate about women’s reproductive rights shows how shallow its progressive status is, and how patriarchal and conservative it actually is. Or, perhaps, how just insanely greedy for votes politicians are. The issue of abortion is not to be dealt with lightly, but it surely must be dealt with. It cannot be simply a matter of being either pro-life or pro-choice, because being pro-life could also result, as has happened not only once or twice, in the unnecessary death of the pregnant woman.

We are so obsessed with being either one or the other that we fail to realise that there can be many other options we could consider. Not to mention that we are stubbornly making use of imported slogans which have not been adequately transposed onto Maltese culture and reality. We have not yet discussed these issues in Maltese, this battle has not yet been fought in our own language, on our territory, nor have we analysed these questions thoroughly from a local and historical point of view.

There are so many stories being told that we have not yet brought together and poured into one receptacle to make sense of it all, and to think about all this before we start judging, accusing, calling each other names, or underhandedly manoeuvring the entire debate in order to win a few votes. Marta Marta chooses to listen before it speaks, while it invites all those who should speak to tell us their stories, in their mother tongue. Only then may we, together with them, begin our work to find solutions which are the least harmful to all those involved.

What role does fiction play in addressing society’s shortcomings?

The epigraph in Marta Marta is a quotation by Paul B. Preciado, who invites the reader to: “Cross out the map, erase the first name, propose other maps and other first names whose collectively imagined fictional nature is evident. Fictions that might allow us to fabricate practices of liberty”. Fiction, in this sense, is the means with which we can dismantle all the faulty structures that we might think of as normal or natural – but which in fact are artificial and man-made constructs in themselves and are what oppress us most – in order to fabricate new realities that stem from the imagination, the dream, the bizarre, the wished-for, to give life to that construct, structure or practice that has the power to set us free.

I have always written about the quest for freedom. I know that complete freedom does not exist: human relations, while being indispensable, always impact our freedom, and in our interactions we have to negotiate how much freedom we allow ourselves to give up, how much of it we allow another person to take away from us. In my writing, this negotiation is always at work. My characters always find themselves having to find a way out, to liberate themselves from whatever is keeping them tied down. Writing is a study in freedom.

Would you say that the fact Malta still lacks effective sex education has contributed to perpetuating patriarchal structures?

Sex has always been used as a weapon with which to dominate, silence, oppress, manipulate, judge, accuse, and undermine. Sex is still, to an extent, taboo – not only in Malta – because it is still appropriated by men, still used as a weapon by the strong against the weak. Considered in this way, sex becomes a threat, it is rape, it is a weapon in the mind of misogynists who might not always be aware of their misogynistic attitude. Nor are women always aware that men’s behaviour towards them is harmful and misogynistic, let alone sexually offensive and punishable by law. Yes, education is a keyword here. And it is what is missing.

How do you feel this novel will be received? What do you hope Marta Marta will achieve?

Marta Marta is, first and foremost, a literary work. It deals with questions and debates that many still refuse to engage in: catholic dogmas still shaping our opinions, reproductive rights still lacking, the unnecessary sanctity of the family unit, the outdated emphasis on the role of women as wives, mothers and carers. This continues to insistently repeat itself one generation after another as if there are no other ways of living, which sometimes makes me think of Malta as an echo chamber. Why are we still obsessed with marriage, with having a family?

Surely that is not the only context within which to frame one’s life, nor in which to procreate, should one want to. Literature engages in alternative ways of being. Creative and alternative solutions. In Marta Marta there is not one answer but several, since there are several characters in the novel. The interaction of these characters sheds light onto possibilities of action.

What the novel promotes for sure is to engage in discussion, to stimulate the much-needed debate. And most of all, it promotes the valorisation of diversity, plurality, the moving away from a binary way of perceiving things since the binary has the tendency to position one thing against its apparent opposite. Listening to the voices that remain unheard is very important. Listening, empathising, understanding, working together, in spite of our differing opinions. This is what this novel promotes and what it seeks to achieve.

This polyphonic novel engages five different characters with different points of view in discussion; at times they agree, at others they don’t see eye to eye. To a certain extent this is my way of holding an internal discussion between the seemingly opposing views that I hold. The interactions and discussions between these characters are not very different from, for example, Denis Diderot’s dialogue between two speakers, in his Paradoxe sur le comédien, who hold very different opinions but are both, at the same time, the author himself. I chose to have five characters because I wanted to avoid dividing everything into two, which, as the novel repeatedly shows, is always problematic.

I needed these different voices in order to examine the various themes that this novel is based upon, because this is the best way you can finally understand something that you have been struggling with. You listen to different stories, you weigh different opinions, you lend an ear to voices from different realities, and only then do you dare voice your opinions about the subject.

This is what Marta Marta stands for. The first working title for this novel was Widna (ear) because from the very beginning I knew that the most important aspect in this new tale I was about to start weaving was that of listening. Everywhere you look you see that there is a tendency to speak first, to attack, to judge, to offend, to scold. This novel advocates listening to stories that are entirely different to ours. Listening in order to understand without then trying to change these stories to make them more similar to ours. Accepting the vibrant beauty of diversity rather than blurring everything into one dull colour for our own peace of mind.

The publication of Marta Marta is supported by the National Book Council. The book will be launched during a three-day event at Roza Kwir Gallery in Balzan between April 29 and May 1.

If you’d like to find out more about Maltese literature and lifestyle, check out this review of Kollox Jeħel Magħna, Lou Drofenik’s Big Oak on Little Mountain and the latest Inspector Gallo – Alias.

Affiliate/Advertising Disclaimer: How I Carry Out Reviews

I received no payment for this interview. The opinions expressed here are purely my own and neither the author nor the publisher had any input/control over what I wrote. There are no affiliate links contained within this page.To learn more about my policies and my reviewing process, visit my Affiliate/Advertising disclosure page.